Portfolio. Program. Project. Operations. Most organizations use these words as if they mean the same thing, then wonder why execution feels chaotic. A company wins more work, launches multiple related initiatives, and suddenly starts using big labels like “program” and “portfolio.” But nothing truly changes except expectations. Project managers become the default owners of everything: strategy alignment, benefits justification, stakeholder politics, factory constraints, handover planning, even service readiness. They are still expected to deliver scope, schedule, and cost, while quietly absorbing responsibilities that belong to portfolio decisions, program integration, and operational ownership.

The lesson is not that project managers need to work harder. The lesson is that portfolios, programs, projects, and operations are different mechanisms inside the same value delivery system, and when they are blurred, value leaks. PMBOK 8 frames a cleaner reality: these elements are connected, but they are not interchangeable. Each has a distinct purpose, decision rights, and success measures, and clarity at those boundaries is what protects outcomes, benefits, and long term value.

What PMBOK 8 is really saying with “interconnection”

At a high level, PMI’s definitions still matter. A project is temporary and creates a unique product, service, or result. A program coordinates related projects to obtain benefits and control not available if you manage them separately. A portfolio groups programs, projects, and other work so the organization can maximize value and meet strategic objectives.

But PMBOK 8 goes further than definitions. It insists on the flow of outcomes, benefits, and feedback across the system. In practical terms, this means four things:

First, projects do not “create value” alone. They create deliverables and outcomes that only become value when operations can sustain them.

Second, operations is not just the receiver at the end. Operations influences feasibility, readiness, serviceability, maintainability, and repeatability from the start.

Third, programs exist to manage interdependencies and benefits. They are not simply “big projects.”

Fourth, portfolios exist to make tradeoffs. They arbitrate scarce resources, risk appetite, and strategic timing across programs, projects, and operational needs.

If you want the simple rule: portfolios decide where to invest, programs decide how benefits will be realized across multiple moving parts, projects execute and deliver outcomes, and operations keeps the value alive.

The value delivery system (Direction, Enablement, and Feedback)

PMBOK 8 intentionally avoids presenting value delivery as a simple sequence of steps, because value does not flow in a straight line. Projects do not “produce value” on their own, and operations does not magically convert deliverables into benefits. What exists instead is a system of governance, enablement, use, and feedback, where different parts of the organization play distinct roles and learn from one another over time.

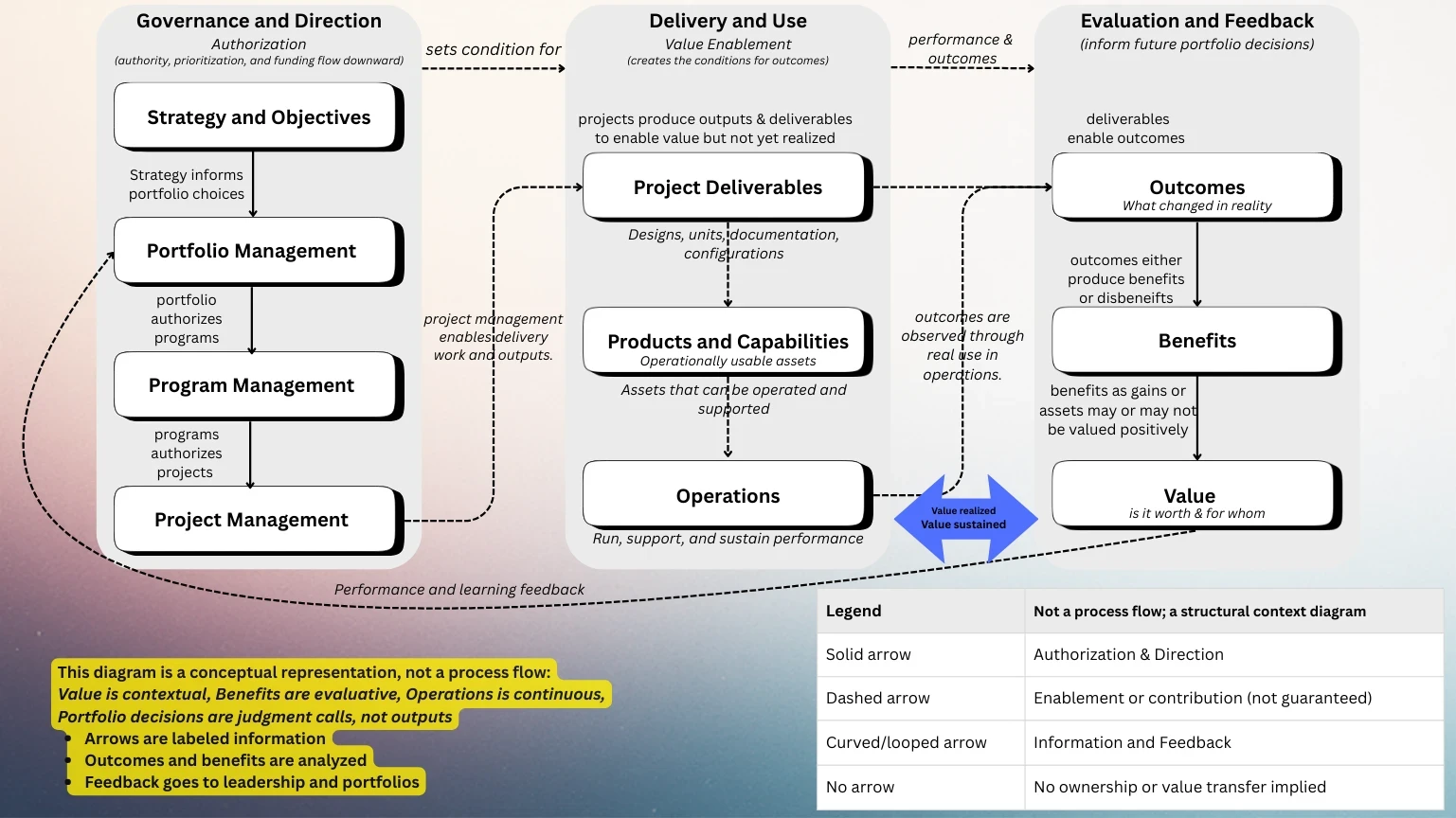

The diagram below represents that system as a structural context, not a process flow. Solid arrows show authorization and direction, where strategy, portfolio, and program governance set priorities and boundaries. Dashed arrows show enablement and contribution, where projects create deliverables, products, and capabilities that make outcomes possible but do not guarantee them. Curved arrows show feedback and learning, where real performance in operations informs future portfolio decisions.

This view matters because it explains why confusion so often arises when portfolios, programs, projects, and operations are treated as interchangeable. Value is contextual and evaluated after outcomes are observed in the real world. Benefits are judgments, not outputs. Operations is continuous, not a project phase. When these distinctions are clear, governance becomes lighter, handovers become intentional, and organizations stop expecting project managers to own value that only the system as a whole can create and sustain.

This diagram represents a system, not a linear process. It illustrates structural relationships and decision boundaries within a value delivery system. It does not represent a sequence of work or guarantee of value realization. Projects enable value but do not guarantee it. Outcomes, benefits, and value are assessed through use in operations and inform future portfolio decisions through feedback.

The roles, in plain language, with decision boundaries

This is where most organizations blur the lines. They either overload project managers with business ownership, or they create layers of leadership that add meetings but do not add clarity.

Here is the clean separation that works well in manufacturing and engineering to order environments.

Portfolio manager: investment and tradeoff owner

The portfolio manager is accountable for selecting and prioritizing the right work, not for running delivery details. They balance strategic objectives, mandatory obligations, risk, and funding, and they decide what gets started, delayed, reshaped, or stopped.

A portfolio manager is not there to “run projects.” They are there to make sure the organization is investing in the right work, at the right time, with the right level of risk. In real terms, the portfolio manager owns prioritization logic and sequencing across major initiatives, in addition:

Strategic alignment and value thresholds

They translate strategy into selection rules. Which initiatives fit the mission now, which ones do not, and what minimum value justifies funding. In practice, they set the criteria for approval and continuation, such as ROI targets, compliance needs, customer impact, margin contribution, or strategic capability building. They also stop work that no longer meets the threshold, even if it is already underway.

Portfolio level risk exposure and capacity

They manage risk and capacity as a system, not project by project. That means seeing concentration risk (too many initiatives relying on the same supplier or the same engineering discipline), balancing “safe” and “bold” investments, and protecting bottleneck resources. When the organization is overcommitted, they force tradeoffs: delay, re-sequence, reduce scope, or cancel, instead of letting everything run late.

Governance cadence for investment decisions

They run the rhythm of decision making. Not weekly status noise, but structured checkpoints where leaders decide what to start, stop, accelerate, or adjust based on performance and changes in the environment. This cadence also ensures decisions are documented, escalation paths are clear, and funding and priority changes are controlled rather than political or reactive.

Program manager: benefits and integration owner

The program manager exists when you have multiple related projects that must act as one system to produce benefits. Program management is explicitly about coordination and interdependencies so the organization gets benefits it would not get if each project ran alone.

A program manager is there when multiple related projects must behave like one system to produce benefits. They reduce the coordination load on project managers and protect the benefits that sit above any single project.

Benefits realization approach and tracking

They define what “success” means at the program level, how benefits will be achieved, when they should appear, and how they will be measured. They track whether outcomes are actually turning into benefits, not just whether deliverables shipped.

Cross project dependencies and integration planning

They own the integrated view. They map dependencies between projects, align sequences, and manage interfaces so one project does not quietly block another. In manufacturing, this often includes design readiness, supplier qualification, test capacity, industrialization gates, and site readiness.

Shared standards

They set and protect common ways of working across projects where consistency creates leverage: governance rules, reporting logic, configuration control, change impact analysis, quality gates, and readiness criteria. This prevents every project team from inventing its own system.

Shared constraints

They manage bottlenecks that no single project can solve alone, such as scarce engineering skills, long lead components, FAT priorities, commissioning resources, or critical suppliers. They drive tradeoffs early so constraints do not become late surprises.

A practical example is the FAT testing area. It is often a hard capacity constraint. You may only have one or two test bays, each test can take hours or days, and only specific technicians, instruments, or test setups can support it. This means production can be ahead and units can be physically complete, yet shipments still bottleneck at testing. That is why strong program managers track FAT capacity at the program level and coordinate priorities across projects, instead of letting each project fight for test time on its own.

Shared stakeholders

They coordinate the stakeholder map across projects so the same leaders, customers, operations teams, and functional groups are not pulled into conflicting decisions. They create one coherent narrative and one decision path instead of repeated negotiations.

Escalation shaping before firefighting

They escalate with options, not with panic. They surface emerging issues early, quantify impacts across the program, and propose decisions that preserve benefits. This is how you avoid last minute hero mode.

Alignment with operations readiness and product lifecycle needs

They design the transition into operations as part of delivery. That includes readiness gates, training and documentation expectations, service and warranty integration, and feedback loops from field performance into engineering changes. Their job is to make sure the program’s outcomes can be sustained, supported, and scaled across the product life cycle.

Project manager: outcome delivery owner

The project manager is accountable for delivering the project outcomes within the approved boundaries. They manage scope, schedule, cost, risk, stakeholders, procurement, quality, and delivery tactics.

A project manager owns delivery inside a defined boundary. Their job is to turn an approved objective into real outcomes, while managing constraints and keeping stakeholders aligned.

Day to day delivery execution

They drive the work forward. They coordinate the team, remove blockers, manage issues as they arise, and keep commitments realistic. In manufacturing, this often means synchronizing engineering, procurement, production, quality, and logistics so the project does not stall between functions.

Project level planning and control

They build and maintain the plan that guides execution, then control performance against it. That includes defining scope, sequencing work, managing schedule and cost, monitoring risks, and using data to forecast what is likely to happen, not just reporting what happened.

Project level stakeholder management

They manage expectations for the specific project. They ensure the right people are informed, decisions are obtained on time, conflicts are surfaced early, and tradeoffs are understood. Their focus is the stakeholder landscape tied to that project’s deliverables and outcomes.

Change control execution within the governance rules

They handle changes properly. They assess impact on scope, schedule, cost, and risk, then follow the governance path for approval. They do not bypass the system, and they do not absorb every change informally. They protect the baseline while enabling justified change through the right decision rights.

Operations or functional manager: sustainability and performance owner

Operations and projects are connected, but they are not the same. Projects create change in a unique context. Operations sustains performance through repeatable processes and service levels. If you want a deeper comparison with practical examples, read Operations vs Project Management.

Running the process or product in steady state

Production planning, daily execution, throughput, quality control, staffing, and meeting service levels.

Sustaining performance and reliability

Preventive maintenance, troubleshooting, repairs, calibration, and keeping the system stable as conditions change.

Customer support and service ownership

Responding to issues, managing SLAs, field service scheduling, and handling escalations as an operational process, not a project fire drill.

Warranty and spare parts execution

Managing claims, spare parts inventory, repair loops, and ensuring the support model is actually workable.

Configuration control in business as usual

Keeping track of what version is installed or shipped, managing approved updates, and preventing uncontrolled variations.

Continuous improvement and cost control

Capturing recurring defects, eliminating root causes, improving cycle time, reducing scrap, and standardizing best practices.

Operational reporting and KPIs

Measuring the outcomes that prove value is real: uptime, defect rates, lead time, first pass yield, energy performance, service response time, warranty cost, customer satisfaction.

Feeding learning back into the value delivery system

Operations becomes the “truth source” that informs the next portfolio and program decisions: what to invest in, what to stop, and what must be redesigned.

Operations does not want your schedule. Operations wants readiness.

In a field service–driven business, readiness means the conditions operations needs to run, support, and sustain the outcome without relying on the project team. In other words, readiness is the point where the unit can leave the project world and enter service without ongoing project intervention.

After readiness and formal handover, operations owns everything that keeps the outcome performing in the real world, day after day, without needing the project team to “babysit” it.

Readiness means commissioning and SAT acceptance criteria are clear, the as-built configuration is controlled, and documentation is complete. Service teams know what was installed, how it was tested, and how it is supposed to perform. It also means the warranty pathway is defined, spare parts and escalation routes are known, and the handover includes training, troubleshooting guidance, and clear ownership for what happens next.

If these elements are missing, field service pays for it in overtime, rework, customer escalations, and long-term reliability damage. The cost is not only financial. It is reputational, because the customer experiences the gap as a failure to support the product, not a failure of a project plan.

This is also why progress tracking should not be limited to task completion. What matters is not what is “almost done,” but what is truly ready. A practical way to support this visibility is to track readiness the same way you track scope, using clear indicators that show what is accepted, what is tested, and what is still pending. Burnup and burndown charts can help when they are used to visualize real completion, not optimistic percent-done reporting.

Key takeaway

Even if warranty service is “not in the project,” the project still has to design the handover so service can run it. That is why operations wants readiness, not your schedule.

What field service operations owns after SAT and commissioning

After SAT and commissioning acceptance, the project stops owning delivery, and field service operations takes ownership of reliability, response, and warranty performance over time.

Warranty execution as an operational system

Claims intake, triage, approvals, replacement parts, return logistics, repair decisions, vendor claims, and closure. This is not a project task. It is a repeatable service workflow.

Incident response and customer escalations

Hotline support, response SLAs, technician dispatch, escalation paths, and the communication rhythm with the customer.

Corrective maintenance and troubleshooting

Diagnosing faults, performing repairs, validating performance, documenting root causes, and restoring service.

Preventive maintenance framework

Maintenance schedules, checklists, technician procedures, and coordination with site access windows.

Spare parts and service inventory strategy

Stock levels, reorder points, critical spares lists, lead times, substitutions, and obsolescence management.

Configuration and asset history in the field

Tracking what is installed where, serial numbers, firmware versions, approved updates, retrofits, and service bulletins.

Continuous improvement feedback loop

Turning recurring field issues into engineering change requests, supplier corrective actions, updated test procedures, training updates, and revised commissioning checklists.

Contractual service compliance

Ensuring service activities, documentation, and timelines meet contractual obligations during the warranty period.

Where PMO fits without becoming an extra layer

A PMO is not a role. It is an organizational capability that centralizes methods, governance, performance reporting, and enablement across portfolios, programs, and projects.

In a healthy model, PMO does not replace portfolio managers or program managers. It supports them by making decision quality higher and decision time faster.

In practice, PMO is where you should park:

- governance frameworks and decision rights

- templates, standards, and integrated reporting

- coaching, audits, and capability building

- portfolio and program performance visibility

When PMO is unclear, project managers get buried in reporting. When PMO is strong, project managers spend more time leading delivery and less time rebuilding governance from scratch every month.

When you actually need a program manager in a growing manufacturing company

You need a program manager when your organization starts paying the “multi project tax.” That tax shows up as duplicated planning, competing priorities, supplier chaos, inconsistent design decisions, and operations readiness being handled too late.

Common triggers in engineering to order manufacturing include:

First, you have multiple projects for the same product line or customer segment and they share design rules, suppliers, test methods, and commissioning constraints.

Second, you are managing interdependencies where Project A’s deliverable is Project B’s starting condition, and delays create a chain reaction.

Third, benefits are not tied to a single project. Benefits come from combined outcomes, such as standardization, reduced lead time, improved reliability, or a repeatable commissioning playbook.

Fourth, operations readiness is becoming a strategic risk, meaning service, warranty, and field performance are impacting reputation and margins.

When these are present, a program manager is not bureaucracy. They are a pressure relief valve.

What the program manager should own

Imagine a manufacturing company delivering CRAH units for hyperscale datacenters. Each customer project looks like a “project,” but the organization is really building a long lived capability: product variants, manufacturing repeatability, supplier qualification, FAT standards, commissioning playbooks, and warranty learning loops.

That is a program environment.

Here is what a strong program manager can own to reduce the load on project managers, while improving governance and operations integration.

Benefits management and the logic of why the work exists

A program manager should own the benefits management plan because benefits typically sit above individual project boundaries. Individual project managers deliver outcomes, but the program manager connects outcomes to measurable benefits across the program.

Examples of program level benefits for CRAH:

- reduced cycle time from order to shipment

- improved first pass yield at FAT

- reduced site commissioning defects

- improved reliability in first 90 days of operation

The business case and investment narrative

In growing manufacturing companies, project managers often inherit a weak business case and are forced to justify decisions midstream. A program manager can own a program business case that frames investment logic and tradeoffs once, then cascades it into projects.

This is especially useful when sales keeps changing priorities, or when engineering wants to pursue technical perfection that does not move program value.

Chartering that creates consistency instead of chaos

Project charters in a program should not be reinvented each time. A program manager can define a charter standard with the non negotiables:

- value hypothesis and success criteria

- boundaries with operations and service

- design authority and decision rights

- escalation paths for customer change requests

This does not remove ownership from project managers. It gives them a stable playing field.

Integrated master planning across projects and operations constraints

In a CRAH program, the critical path is rarely inside one project. It is inside shared constraints: long lead components, FAT capacity, engineering bandwidth, packaging lanes, and field commissioning windows.

A program manager should own the integrated view. Not to micromanage schedules, but to protect the system from local optimization.

Shared risk management and systemic issue control

Project risk registers tend to repeat the same risks. Supplier delays. design churn. test failures. site readiness. warranty claims.

The program manager should consolidate systemic risks, assign owners, and drive preventive actions that no single project manager has the time or authority to enforce.

Operations readiness as a designed outcome, not an afterthought

This is where PMBOK 8’s “interconnection” becomes real.

A program manager can define what “ready for operations” means across the program:

- training and documentation standards

- spare parts strategy and service procedures

- handover gates and acceptance criteria

- feedback loops from warranty into engineering change control

To see the wider PMBOK 8 context around how the landscape is evolving, refer to my article Project Management Landscape Analysis.

Common failure patterns I see in engineering to order environments

Treating a program like a big project

The symptom is a beautiful integrated schedule, but no benefits plan, no adoption tracking, and no operational change ownership. Projects finish, benefits do not.

Confusing resource allocation with resource availability

Portfolio level decisions are made as if people are interchangeable. Then execution collapses on bottleneck skills.

Handover happens at the end

Operations is invited late, training is rushed, documentation is incomplete, and service learns on the customer’s site. This is where reputations get damaged.

PMO measures activity, not outcomes

The PMO reports on templates used and meetings held. Nobody can explain whether value is being protected.

Local optimization wins over global value

Each project hits its own milestones, but the product lifecycle suffers: too many variants, too much technical debt, too much support burden.

A simple governance model that aligns all four layers

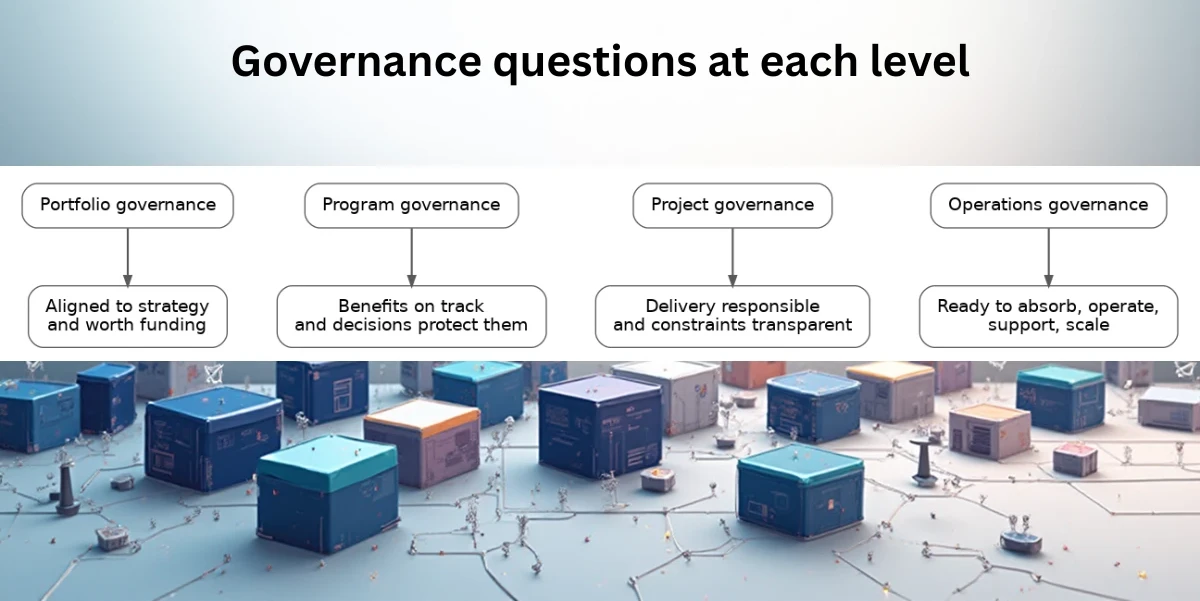

If you want a practical model that works without bureaucracy, align governance to four questions:

Is this work still aligned to strategy, and is it still worth funding

That is portfolio governance.

Are we still on track to realize the intended benefits, and what decisions are needed to protect them

That is program governance.

Are we delivering the planned outputs responsibly, and are we managing risk and constraints transparently

That is project governance.

Are we ready to absorb, operate, support, and scale the outcome without breaking the business

That is operations governance.

Notice what is missing: endless meetings. Governance is not about meeting frequency. It is about decision clarity, timing, and accountability.

The common failure mode: assigning program work to project managers

If your project managers are writing business cases, defining benefits, creating governance from zero, coordinating cross project dependencies, managing shared supplier strategies, and negotiating the operating model with service, you do not have a project management problem.

You have a missing program layer.

When you add the program manager correctly, you do not create more meetings. You reduce duplicated effort and you raise decision quality. Project managers get to focus on delivery, and operations gets a predictable interface.

Decision Rights That Prevent Confusion

If you want less chaos, start with decision rights. At the portfolio level, leaders approve what gets funded, what gets prioritized, what starts, what waits, what gets stopped, and what gets resourced. At the program level, the focus shifts to benefits and integration: what targets we are pursuing, how projects must coordinate, and which tradeoffs protect the overall outcome. At the project level, the project manager owns execution within the agreed boundaries and escalates when those boundaries are at risk. Operations then takes ownership of readiness, sustainment capability, and steady state performance once the outcome must be run and supported. You can keep the organization flexible, but you cannot keep it ambiguous. Ambiguity is expensive.

PMP candidates: how this shows up on the exam without trick wording

On the PMP exam, you are often tested on the intent, not the dictionary line.

Portfolio is about selecting and prioritizing work aligned to strategy.

Program is about coordinated management to realize benefits and manage interdependencies.

Project is about delivering a unique result in a temporary effort.

Operations is ongoing work that sustains the business.

If you can explain decision rights and success measures at each level, you will answer these questions correctly even when the scenario is worded creatively.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a program just a large project:

No. A program is not defined by size. It exists to coordinate related projects and activities so the organization can realize benefits and control interdependencies in a way that managing projects individually cannot.

Do you always need portfolio management:

Not always as a formal role, but every organization still makes portfolio decisions. The real difference is whether those decisions are explicit, governed, and value based, or informal and reactive.

Where does operations management connect to projects:

Operations connects to projects through readiness, constraints, and sustainment. Projects create outcomes in a unique context. Operations sustains performance and keeps the value alive over time. If you want a deeper comparison with practical examples, read Operations vs Project Management.

Closing thought

You can deliver every project milestone and still fail to deliver value. That is what happens when portfolio decisions, program integration, project execution, and operational ownership are blurred into one overloaded role, usually the project manager. PMBOK 8 is not asking us to memorize nicer definitions. It is asking us to manage the system that creates value.

Portfolios exist to make investment choices and tradeoffs. Programs exist to protect benefits by managing interdependencies and shaping decisions before problems become firefighting. Projects exist to deliver outcomes in a unique context. Operations exists to sustain performance and turn outcomes into long term results. These elements are connected, but they are not interchangeable. When decision rights are clear and the handover is designed early, delivery becomes calmer: fewer conflicting priorities, fewer late surprises, and less value leakage after shipment.

This is especially true in engineering to order manufacturing. When a company scales a product line coordination is not a side task. It becomes a capability. The organizations that win are the ones that build the program layer intentionally, align it with operations readiness, and govern the portfolio as a real investment system, not a status reporting routine.

This is the work I focus on: helping PMOs and delivery leaders design practical portfolio and program governance, define role boundaries, build benefits tracking that actually matters, and create an operations handover that protects outcomes after the project ends. If your teams feel stretched, it is rarely a motivation problem. It is usually an operating model problem, and it can be fixed with clarity, discipline, and a system level view of value delivery.

If you are a PMP candidate, do not memorize these terms as definitions only. Use them as a decision model. Ask who owns the investment choice, who owns benefits and integration, who owns delivery, and who owns sustainment after handover. That mindset will serve you on the exam, but more importantly, it will serve you in real governance conversations at work.